I’ll never go abroad 1960 – 1965

Introduction

Do you ever regret making a comment years ago, which proved how stupid and wrong you where when you look back over your life?

I was about thirteen at the time and ‘studying’ French. On the completion of the final examination the class results positioned yours truly second to bottom in a class of forty. I was not very good, nor was I interested in the French language. I can remember the teacher, when discussing my poor effort, asking what would I do if I ever went abroad. The thought of going abroad was so far out of my comfort zone that I remarked that ‘I’ll never go abroad’.

Nearly sixty years later, after visiting more than sixty-five countries, I still feel that I should bury my head in the sand, because of my stupid remark.

1960

During school assembly in March of 1960 the headmaster asked if anyone wished to take an examination to enter a merchant navy officer-training establishment called HMS Conway.

I discussed this opportunity with my parents, because I would have to leave school any way later in the year having reached sixteen. Most of my friends had left the previous year (when they were fifteen) to take up apprenticeships, working in the local shipyard, Port Sunlight soap works or Stork Margarine . None of which attracted me, so I stayed on for another year to gain nationally recognised certificates in various subjects.

My parents agreed that I could attempt the examination, which required a weekend at Plas Newydd (HMS Conway’s facility) on the island of Anglesey, in North Wales. The examination had several written parts as well as an oral examination. I suppose the oral part was to see what I looked like, and if I was aware of world events.

Several weeks after attending Plas Newydd I received a letter of acceptance, and my father received notification that I had won a scholarship, because Conway was a fee-paying school. My parents had to find the money for uniforms and books, but the main fees were part of the scholarship.

I suppose it was ironic that I was about to attend HMS Conway, which was a naval training establishment that used to be a wooden sailing ship moored in the Mersey, but was now a shore establishment in Wales. As a small child I had been told of the ships in the River Mersey, and that small naughty boys would be sent to one of them as a punishment. For the children of Birkenhead at the time, none of us wanted to be sent to one of ‘those’ ships. Now I was going to one as a volunteer.

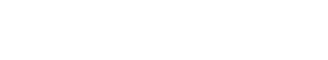

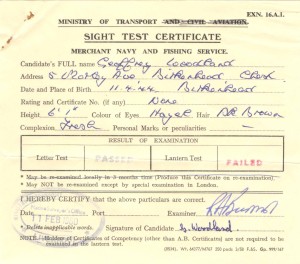

Before any of this could take place I had to take an eye test at Liverpool, because all merchant navy deck officers had to have 20 / 20 vision and were not allowed to wear glasses. Besides the traditional word chart and the colour chart, to make sure I wasn’t colour blind (a deck officer could not be colour blind) I was given a test in a very dark room, and I was required to spot red, green and white pin pricks of lights as if I was on the bridge of a ship. The positioning of the lights would allow a lookout or officer to know the direction of the other vessel.

I was able to see some of the lights, but not all, so I failed the test.

As I left the testing centre I was given a form that stated that I had failed, but if I wished to challenge this result I could apply to London for a more detailed test at my own expense. If I were successful in the London test, all of my expenses would be reimbursed.

After discussing the failed eyesight test with my father, I borrowed £5.00 from him for the return train ticket to London and the second eye test fee. I passed the London test.

On returning to Liverpool I visited the eye-testing centre to let them know that there was nothing wrong with my eyes. They asked me to take the test again, which I did, and failed again.

At this point someone had the bright idea to switch on the light in the testing room. I had been placed on a wooden box to view a screen, which showed the red, green and white lights. Because of my height (over 6 ft) and being on top of the box this made my eye level to be just beneath a cross-beam (the testing centre being in a basement). In the dark one has a tendency to sway slightly, because you do not have a point of reference on which to focus. The swaying was enough for me to see the lights some of the time, and not be able to see them other times, due to the beam! It made me wonder how many others had been failed, and accepted that they had an eye ‘problem’, and perhaps never went to sea, and ended up in a job that they hated.

At least I collected my £2.00 reimbursement for the second eye test, my train costs and 7/6d for my trouble.

Summer 1960

The first adventure abroad was when I’d just turned sixteen (1960). I’d gained a scholarship to HMS Conway nautical college, and I was due to join this establishment in September.

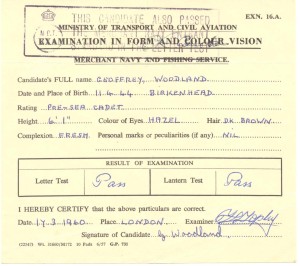

A family friend (a school teacher) asked me to accompany him in August to help shepherd a group of fourteen to sixteen year old students during a YHA (Youth Hostel Association) trip around Germany. Because I was tall for my age, looked older than my years, and didn’t attend the same school as the other students, the schoolteacher considered me ideal as his ‘offsider’. Of course I didn’t have a passport, but at that time one could obtain a twelve-month passport for a large discount on the ten-year passport. The British were just starting to take European holidays after the financial hardships of the post war 40’s and early 50’s, and YHA was cheap, but cheerful.

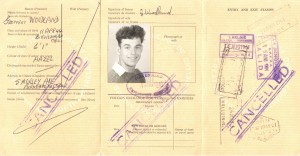

The pictures show my second one-year passport

(The first passport was issued for my 1960 holiday)

We travelled by coach from Birkenhead to Dover, which is on the south coast of England, where we boarded a ferry to Ostend, Belgium. The trip from Birkenhead took us hours and hours, even though the new M1 motorway between Birmingham and London had opened the previous year. The one thing I always hated was bus travel – it made me ill, and I was very glad of my Kwells travel tablets. Even the smell of the inside of a bus today brings back bad memories.

Due to the very long journey from Birkenhead to Ostend, the group leader had booked us in to the Zeebrugge youth hostel, which was a short distance along the coast from Ostend. The one thing I do remember about Ostend was a particular coffee bar, which had a jukebox. Jukeboxes were not new to us, but we’d never seen a jukebox linked to a TV screen. For one Belgium franc (well before the EEC and the Euro) we were able to play popular songs and watch the singer on the screen. This is the only memory I have about my first visit to a foreign city.

Zeebrugge was more interesting because it has a strong link to Birkenhead and Merseyside. During WW1 in 1918, the Daffodil and the Iris (both Mersey ferries) took part in the commando raid to sink obsolete ships in the main channel at Zeebrugge, to prevent German vessels leaving port. Although badly damaged, and with many killed and wounded, the two ferryboats managed to return to England, and eventually the Mersey. In honour of their contribution to the raid King George V conferred the pre-fix ‘Royal’ on both ships; they became the ‘Royal Iris’ & the ‘Royal Daffodil’. The second descendant of the ‘Royal Iris’ came in to service in 1951, and it was in 1965, on this ‘Royal Iris’, that I danced with a young girl who would later become my wife.

Our transport around Germany was by rail, which was electric, where as the British system was a mixture of steam and diesel engines. The high-speed trains of Belgium and Germany were exciting to us, but we did miss hanging out of the window and breathing in the unique smell of steam and smoke from the engine. Even so, the German trains had a character of their own, modern, fast and efficient.

It was common for YHA members to walk or cycle from hostel to hostel, but the distances between each of our stops made this mode of transport unacceptable. Our first stop after leaving Belgium was Cologne, which I found to be an interesting place. In 1960 the war had been over only fifteen years so growing up in the UK, at that time, most of the Germany city names were very familiar. One place that we didn’t hear much about, but knew of from school, was Bonn, which at that time was the de facto capital from 1949 to 1990. The old capital, Berlin, was under the control of the four powers, America, Britain, France and Russia.

I found Bonn to be a dull city, and was not sorry to leave the place, via train along the banks of the Rhine to the spa town of Bad Honnef. ‘Taking the waters’ was all the rage, and of course we had to try the water, and from memory I was not all that impressed, because I didn’t know what to expect and the mineral taste was completely different than the tasteless water that came out of the tap at home. On the other hand it was new to me, it was different and it was foreign, so I drank another glass of the famous Bad Honnef water.

Colour film was too expensive for a sixteen year old, but I could still hang out of the window for pictures of our train journey across Germany.

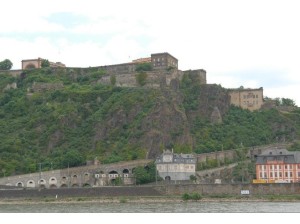

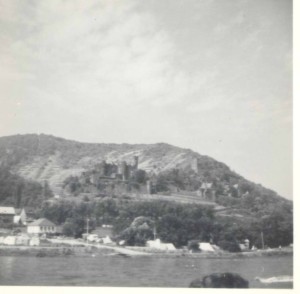

A further short rail trip from Bad Honnef, took us the Koblentz (or Coblenz). The YHA facilities were located in the castle and overlooked the confluence of the Moselle and the Rhine. I was fascinated that I could actually see the two different waters, because they were naturally coloured – the Moselle was green and the Rhine blue, and after they had met they became the normal brownie river colour that we all recognise. I can still remember the view nearly sixty years later.

The Moselle flowing in to the Rhine.

The photograph has been taken from the area of the YHA, around fifty years later. I’m sorry to note the absence of colour in the water.

We enjoyed our stay in Koblentz, the town being ‘old German’ buildings (I don’t remember any modern buildings), cobbled streets, heavy rounded glass shop windows, a real pleasure of a place to just stroll around and absorb the atmosphere. Of course I was too young to drink alcohol, but we made do with ginger beer (it was the same colour as real beer) so we would sit in the sun and watch the young German girls as they promenaded around the main square.

Koblentz YHA (left picture) was inside this castle

Bacharach, further up the Rhine again, was our next stop, and it was quite different from the other towns and villages that we had visited. The YHA was located within Bacharach Castle, which from memory was very different from the Koblentz castle.

I do remember one evening when many of the students were in the Bacharach Great Hall, which was heated by a fire in a huge sandstone pillared grate, when a young man dressed in leather shorts with shoulder straps (braces if you are English, and suspenders if you are American), thick leather climbing boots, and socks folded down around his ankles entered the room dragging a long heavy rope behind him, and shouting for help due to the rope’s weight. I assumed that this person was the YHA manager or was employed by the YHA. A number of us ran over and helped drag the rope in to the hall, where we were instructed to lay it out in a single long length. We were about to take part in an international tug of war!

The tug of war was to be a knock out contest, and was to be in front of the large grate as the flames danced up the chimney. The overhead lighting was dimmed so that the fire illuminated the two teams trying to pull each other over a marker chalked on the wooden floor.

The rope didn’t have the feel of ‘real’ rope; it was very smooth and softer than the rope I would handle later when I was at sea. The British team asked me to be the anchorman due to my size. Using my limited knowledge of knots, taught to me by my father, I tied a Bowline knot to secure myself to the rope. This knot created a loop in the rope, which I put around my chest. Regardless of the weight put on this knot it would not tighten further than the original pressure when it was created, so protecting me from being injured. Thanks Dad!

It was great fun, and because the German members were the greatest number, they had more bodies from which to choose and so won each heat against all other countries. It wasn’t long before the larger boys from different countries agreed to join an international team to compete against the German team. The international team won three out of five ‘pulls’ or should it be ‘tugs’. Perhaps the German team was tired after defeating all the other nations independently, but they couldn’t hold out against a combined international team. Every time I see the film ‘Where Eagles Dare’, with Richard Burton & Clint Eastwood, and the scene where all the main characters are seated around a long table across from a large fire in a medieval fireplace, I think of Bacharach and the tug of war.

From Bacharach we sailed back down the Rhine towards the coast. The name of the paddle steamer vessel was the ‘Bismarck’, and I can remember making the comment that I hoped we didn’t suffer the same fate as the original ‘Bismarck’ in 1941.

What more could a teenager want, but to be aboard a wooden decked river boat with the sound of the steady throb of the engine, the paddle wheels slapping the water as we glided down river, with pale smoke from the vessel’s funnel drifting towards a clear blue sky. All was well with the world as I leaned on the rails and viewed the vineyards, castles, scenic Germanic buildings, which I am sure are still in use today.

Bacharach was our last ‘new’ place before making our way home, via Bonn, Ostend, the ferry and the long bus ride to Merseyside.

River traffic and castles as we sailed down river.

September of 1960, I joined HMS Conway Nautical Training College, so further travel that year came to a stop.

Travel around the UK didn’t stop, because I was picked for the 1st XV rugby team, which entailed travelling to ‘away’ match in London, Pangbourne, Merseyside and many parts of Wales. Would one consider visiting Wales to play rugby, as a ‘visit abroad’ for an Englishman?

We had three terms – autumn was September to Christmas, winter was January to March and summer, April to July, and rugby was played from September to the end of March. I have never reached the level of fitness that I did during my two years at the Conway.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

1961

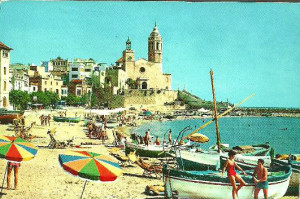

In 1961 I was invited once again to accompany my friendly schoolmaster for another trip to Europe, but this time it would be southern Spain, staying in a hotel rather than YHA. We’d moved up market.

We used the train service this time from Merseyside to Dover, and had our fill of the smell of steam and blackened smuts suspended in the clouds of smoke from the engine.

A ferry carried us to Calais, in France, where we boarded a coach to take us to Sitges, in Spain.

Our coach crawled through the late evening town traffic until it came to the motorway (freeway) at which point the driver flawed the accelerator and we were truly on our way to sunny Spain.

The excitement of the trip began to fade as evening became night, and the chatter of the students drifted in to sleep. I tried to sleep, but the movement of the coach and the smell of the plastic seating, caused my travel sickness to return.

The occasional whisper as a student pushed another’s head from flopping on their shoulder would interrupt the steady throb of the coach’s engine. Every couple of hours the driver would take a rest by calling his colleague who sat close to him. During the change over process the coach didn’t stop. The current driver would stand gripping the steering wheel, while keeping his foot on the accelerator; his mate would slide in behind him, place his foot on the accelerator, and grab the steering wheel. The first driver would then move away to rest and sleep. It was a sight to see, and very smoothly accomplished so that the speed (about 100 km / hour or 60 mph) didn’t alter. I’m not sure how many of the students watched this change over; perhaps it is just as well that many, if not all, slept through the process. Seat belts were still in the future.

The single deck coach was modern for the 1960’s, but nothing like today’s intercity coaches. The only time we stopped during our road trip to Spain was for toilet breaks. If anyone required a toilet the driver would be warned and the passenger would have to ‘hold on’ until we reached the appropriate place. On stopping everyone was told to leave the coach, even if they didn’t wish to visit the toilet, and walk around the car park area. It seemed a good idea at the time, but then we had the problem of counting everyone back on board in the half-light of petrol stations or a café’s poor outside lighting. Our schoolteacher leader would count everyone at least twice, and then get me to count the students again, once all were on board. The last thing he wanted was to write to a parent and tell them that their daughter was lost somewhere in France.

The total distance from Calais to Sitges is about 1350 kms (865 miles) and from memory it took us around fifteen hours. Although most of the journey had been completed during the night, eventually dawn filtered through the curtains covering the coach’s windows. As it grew lighter more and more curtains were pulled aside and we could see the Mediterranean Sea. A calm, startling blue sea sparkled as a cheer swept the coach from the excited students. The border between France and Spain must be close. The excitement was infectious as we all peered through the left hand side windows. My travel sickness forgotten, Sitges was round the next bend . . . or was it?

It was not until lunchtime that we arrived in Sitges only to be told that the hotel did not have enough rooms for all of us, and they (the hotel) suggested that two ‘guests’ sleep in a small apartment near the hotel. Our leader asked if I, and the other ‘helper’ (a friend of mine) would mind sleeping in the apartment, because he wanted to keep an eye on the younger members of our group, in the hotel. We were quite happy to agree because the whole idea was a new adventure for us.

The apartment was close to the hotel and it was a short walk each morning for us to join the main group for breakfast.

Living ‘out’ did allow us to sample the odd place that we might not have visited if we had been in the hotel. One place we sampled was a room, which along three walls had wooden barrels of alcoholic liquid made from various fruit, from bananas to grapes. The liquid was quite ‘thick’, more like a heavy port than a quaffing liquid. The storekeeper allowed us to sample some of the barrels, in the expected hope that we would buy a bottle or two. Of course at seventeen we were happy to try as many as possible, until the shopkeeper realised that we didn’t have any intention of buying anything. We were asked to leave. The one sample that sticks in my mind was a yellow silky drink that had quite a kick; it was made from bananas. The sampling amounts we were given were not very large, perhaps a tablespoon, but after sampling several we did feel a little off colour.

Sitges is located on the Mediterranean coast of Spain, about thirty-five kilometres south of Barcelona. It was a very pleasant town with a church on a headland that jutted out in to sea. The beach was very clean, and not too crowded. I have no idea what the place looks like today, but I have happy memories of Sitges.

Trips were arranged to various places of interest including a bullfight at Tarragona, sixty-five kilometres south of Sitges. I believe the authorities have renovated the old bullring and now it is used for Castells, or the building of human towers. Also music festivals and sporting events are held there today. I don’t know if it is still used for bullfights. In a way I am glad that I saw the bullfight, because the experience put me off bullfighting for the rest of my life. At the time of my visit to the bullring everything was new and exciting, including the next experience.

While in Sitges it rained heavily one night, the first time in months. The day after the rain my friend and I met a group of semi professional boxers from Liverpool. They had camped in a dry riverbed, and all was well for a few days, until it rained and the river washed away or damaged much of their equipment. They had ridden to Sitges on their motorbikes.

We recognise some of their names, and once they found out that we were from Merseyside (Birkenhead is across the river from Liverpool) they asked a favour of us. They wanted to ‘camp’ in our apartment for a couple of nights while they sorted out their gear and fixed their motorbikes. We had plenty of space and thought that it wouldn’t be a problem, so they moved in to the apartment.

The boxers went out on the first evening and my friend and I had our meal in the hotel with our group of students, and returned to the apartment to go to bed, which was around 10.00 pm. The sun, sand and seawater had tired us out.

The next thing I knew was when a rifle butt struck me in the back. From a deep sleep I was brought suddenly awake and tried to protect myself. A soldier, in a green uniform, was indicating that we should get up and get dressed. We did, very quickly. While getting dressed I could see another soldier looking over the living area balcony in to the street. Before we went to bed we had two potted palms, one each end of the balcony. It appears that our boxer friends had returned from a night out and decided to have a pot plant competition (the pot plants were very heavy) to see how far they could be thrown from the balcony.

This picture illustrates the small balconies and the narrow Sitges streets.

The soldier pushed my friend and I down to the street and motioned for us to pick up a broom each and to start sweeping the street. He had a rifle and I had a broom – I began to sweep the street. The boxers had been ‘corralled’ along a wall by additional armed guards.

It appears that after throwing the potted plants the local neighbours called the police, who, when they arrived met the drunken belligerent ‘boxers’. Not wishing to get in to a fight, the police called the army, (General Franco was still in charge of Spain). Shortly afterwards my friend and I were sweeping the street.

The army tried to get the boxers to start sweeping up their mess, but when a guard pushed one of the boxers, the boxer threw a punch and flattened the guard. That was it!

We were quickly ordered in to a line and surrounded by armed troops and marched off to the local police station. The boxers treated the whole thing as a joke and started to sing ‘Working on a chain gang’ and other prison type songs. My friend and I were not at all happy at being included with our drunken acquaintances.

At the police station I asked to see the British consul, but the Spanish police were not having anything to do with consuls, particularly a British consul. At that time the Spanish government was demanding that the British return Gibraltar to Spain, so the police were quite happy to lock us all in a small cell below street level. The cell was square shaped with three solid concrete walls, the outer wall having bars high up over a small window, where we could just see the pavement if we held on to the bars and pulled ourselves up to check the street outside. The fourth wall was a wall of iron bars, which also contained the door. The cell was not large enough for us all to sit down (nothing to sit on anyway) and the toilet was a hole in the corner of the cell on the outside wall, without the usual cistern, pan and seat.

The two side concrete walls had graffiti scrawled across them, and some Spanish words, which I couldn’t understand. It was a depressing place and it smelled of urine and other waste products. We organised ourselves to be as far away from the toilet area as possible. My friend and I were left in the corner near the meeting of the iron barred door and the concrete wall.

The boxers kept singing, for what seemed hours, until they eventually stopped as they slowly sobered, and realised where they were.

On the floor we used a large oblong piece of bread as a football, and tapped it from one to another. Not that we could kick it far, considering the smallness of the cell, but it did help to pass the time. As time passed I tried to sleep standing up and then I tried as I squatted down, but this brought too much pressure on my knees forcing me to stand again.

The grey light of dawn brought some relief, because in the cell block there was only one small light bulb that glowed by the main door into the underground cell area. Perhaps we could make someone understand our need for the British Consol in daylight.

As daylight strengthened the outer door of the cell block was unlocked and a guard entered. We asked for food and something to drink. The guard pointed to our ‘football’ and bent down to turn on a water tap over the toilet. Leaning over the toilet we were just able to catch a single handful of water. The other hand we used to balance ourselves away from the open toilet hole. The cold water was welcome, but I was concerned that it might not be normal drinking water so most of mine went on washing my face to try and get rid of the tiredness.

The now sober boxers, asked to see the officer in charge, and when the policeman, who spoke English, arrived, they spoke up and told him that we had nothing to do with the damage. It was obvious that my friend and I were much younger than the boxers, and after a few minutes the officer opened the cell door and let the two of us out. He relocked the door just in case the boxers thought of escape.

We were taken upstairs and told to stand in front of the officer’s desk. He then lectured us and told us to behave while in Sitges, and that he didn’t wish to see us again. We quickly agreed with everything he said, although later I considered that we were only guilty by association, and innocent of any wrongdoing, unless helping fellow British travellers was a crime. At the time we would have agreed to anything just to get out of that stinking cell.

We were able to get back to our apartment for hot showers and a change of clothes, before making our way to the hotel for breakfast. We acted as if everything was normal, even though we did yawn a lot. I didn’t tell our leader because I didn’t wish to add to his worries, nor did I want our adventure to get back to our families.

It must have been ten or fifteen years later that I told my mother the details and I still have my doubts that she believed me.

The rest of our time in Spain was sightseeing local places of interest, sun bathing on Sitges beach and eating. All holidays come to an end and it was another fast drive to Calais, ferry to Dover, and the train home with a great suntan and the experience of being a gaolbird.

The Spanish holiday was my last overseas trip for over a year, because I knew that I had final examinations before leaving HMS Conway in 1962 and the results of this examination would determine the shipping company that I’d join – if any shipping company would have me.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

1962

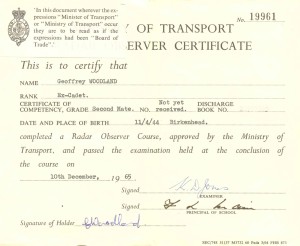

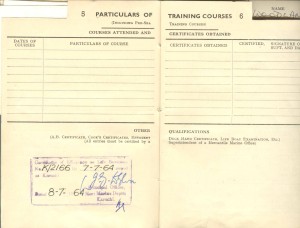

In mid 1962, after two years at HMS Conway, I graduated with a First Class leaving certificate. British India Steam Navigation Company, also known as simply BI, accepted me in August, as an indentured cadet (apprentice).

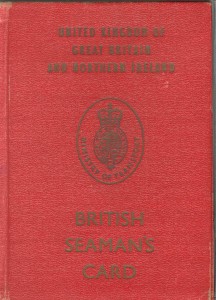

Once I’d been accepted I applied for a British Seaman’s Card and a Discharge Book.

I had the paperwork to prove that I was a sailor, but I’d never been to sea.

In mid September I was order to join a tanker, the Ellenga, on the 12th October, in the River Fal, which was moored just off the town of Falmouth. The vessel had been in dry dock and was about to sail for the Persian Gulf for a cargo of oil. For someone who didn’t have any intention of going abroad I was doing a lousy job of staying in England.

On joining I became one of four cadets, and the other first trip cadet turned out to have been in my class at HMS Conway! Seeing each other helped us to fit in to our new life. Each cadet had his own cabin, and we all shared a Goanese steward who looked after our requirements. I didn’t have any idea before I joined that a lowly cadet would be entitled to the services of a steward!

Later I realised how lucky I was to join BISNC. A Scotsman, William Mackinnon in 1856, had created the Company, and he set certain standards for the benefit of the officers and crew; conversely he expected a high standard of service from his employees. BISNC. was a proud company and highly regarded by both officers and crew. Many of the crew had spent their whole life in the service of the Company, and they considered it a great honour to be in the Company’s employ.

We sailed early afternoon, and as a first trip cadet I was ordered to the bridge and told to watch and observe and not to get under anybody’s feet. This gave me the opportunity to see the British coastline sink lower and lower in to the silver-grey sea, while on our port side the haze of the French coast could just be seen on the horizon. Eventually, both the British and French coast disappeared, leaving us all alone in the Atlantic Ocean heading for the gateway to the Mediterranean, Gibraltar, and then on to the Suez Canal.

I was on the Ellenga for about nine months and all of the cadets worked alongside the crew, because hopefully one day we would be watch-keeping officers and we would be expected to know how many men would be required to do a certain job, and how long is would take.

In addition we were expected to learn Hindi, because that was the language that the crew understood. Many of the crew spoke some English, because they had worked for the Company all of their working lives, but as an officer one was expected to speak Hindi. I still have my Malim Sahib’s Hindustani a book, which includes all nautical terms and words in common use both ashore and afloat, quoted from the front cover. (Malim Sahib = Ship’s officer). I only wish I’d spent more time reading this book.

When I left home my father warned me about being sent for a ‘long weight’ or a ‘bucket full of steam’, so I was well aware of the tricks played by older hands.

One day I was told by the First Officer to get the Cassab from the forecastle store. Remembering Dad’s warning I made my way to the store and lay down on a coil of rope to have a doze. I figured I’d report back in about twenty minutes.

I dozed for a few minutes when suddenly the daylight from the doorway was blocked, and I rolled over to see why. It was the First Officer, and he was not at all happy with this first tripper. It was then that I was told in no uncertain terms that Cassab was Hindi for storekeeper, not some fictional item to take the mick out of first trippers..

My life at a first trip cadet became a mixture of boredom and extreme interest. We were expected to learn the layout of all the deck pipes that carried the cargo oil, including the cross over values to switch oil from one tank to another and the position of the firefighting equipment.

On the other hand we had to take part in chipping paint off the rusted areas of the deck and bulkheads using a small hand held bronze hammer. We used bronze hammers because they were made from non-ferrous metal and would not cause a spark. A spark on a tanker was the last thing anybody wanted, because it could ignite the gas that seeped on to the deck from the crude oil. We used to receive regular warnings of tankers in distress due to gas igniting. I don’t remember ever reading that the damaged vessel survived, the report usually reported that the tanker had blown up due to gas ignition. The reports made comforting reading for those of us chipping away.

Once the bare metal had been exposed we would paint it with red lead paint (in today’s world, H&S would have a fit). After the red lead had dried, we used grey undercoat followed by the white topcoat. A 30,000 ton ship has a lot of metal to chip by hand. Many of the later ships in which I sailed, the cadets and crew used an electric chipper that had several heads spinning at high speed, so making it easier to clean a large area quickly, but those vessel were not covered in gas.

The bane of using the non-ferrous hammer was that it quickly became blunt and required more force to belt the rust away so as to expose the metal deck. It was hot sweaty work in a Persian Gulf summer.

In our free time we studied, via correspondence courses, for our examinations to become deck officers.

The Ellenga took me to some strange places. Our first port of call was Port Said as we transited the Suez Canal. We didn’t stay long in Port Said, just a few hours while the authorities created a convoy to transit the canal. The canal is only wide enough for vessels to go one way, so a group vessel would travel southbound to the Bitter Lakes, or a ‘cutting’ where the southbound convoy can stop and allow the northbound convoy to pass. While transiting the canal local ‘bum’ boats came along side, and those that had the company contract would hitch a ride through the canal; so that when we reached the ‘cutting’ they would carry our mooring lines ashore to bollards. If we passed the cutting we would anchor in the Bitter Lakes. Before the canal was built there were salt valleys in the area, which became flooded after the canal was opened; hence the name of Bitter Lakes.

Mixed with the crew of the ‘bum’ boats we often had trinket sellers and entertainers. The sellers sold souvenirs, mainly to passengers on passenger ships, rather than the crew of tankers. Regardless, once we knew these entertainers / sellers would be aboard we locked everything down – cabin doors, windows, doors to the accommodation and any loose pieces of equipment belonging to the ship. We never locked our cabins at sea, but we did when ‘strangers’ where on board.

During my first trip through the Canal I was introduced to the Gully Gully man, who was an outstanding conjurer. On the main tank deck he had an endless supply of day old chicks, and he could make them appear and disappear, and we (cadets) were only a few feet away from him. We couldn’t see how his tricks were done. He made the chicks appear out of thin air or our shirt pockets; he was very good and would have been top act for a TV show. We paid him as one would pay a street entertainer and when he had covered all of the officers and crew, and considered that he had made enough for the day, he shinned over the side and dropped in to a small riverboat that was following us.

Once we crossed in to the tropics the small swimming pool that we had on the tanker came in to its own. It was the cadets’ job to pump out the water each day around 6.30 to 7.00 am and refill with fresh seawater. Many times we noticed flying fish in the pool; they had ‘flown’ in during the night, perhaps attracted by the deck lights. We would catch the fish as the pool’s water level dropped and keep them in a bucket of sea water. Once we had them all we would present them to either the deck crew or the Chinese ‘Johns’. The Chinese ‘Johns’ where Hong Kong Chinese (Cantonese was their language) and they were either engine room fitters or the carpenter. We cadets had more to do with the carpenter than the engine room fitters.

I don’t know why the Chinese crew members were called ‘Johns’, but perhaps it was due to the first Chinese person to take our British nationality in 1805, was called John Anthony.

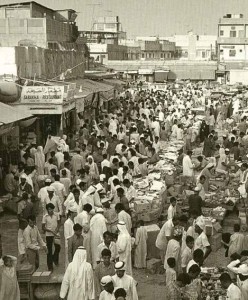

Kuwait is an oil rich kingdom that has its main city named after the country, but we were not to berth at the main city of Kuwait, but Mina Al Ahmadi the oil port a few miles outside the city. At that time they were separate towns, but I think that Kuwait city has expanded so much as to combine Mina as an outer suburb of Kuwait today. Once along side (an oil jetty) we were told that we were not allowed outside of the refinery, and that the perimeters was guarded by armed guards, and a metal fence with barbed wire on the top. Loading 30,000 tons of oil would not take long; perhaps twelve to fifteen hours and the cadets had the job of supervising the loading under the officer of the day. If we had time we would be allowed to visit the ‘canteen’ within the confines of the refinery. This canteen was a corrugated metal building and was restricted to foreign crews only.

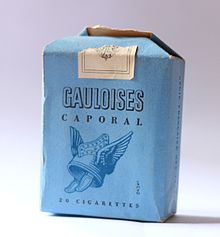

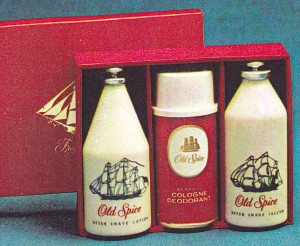

Since joining the tanker I’d learned how to smoke and drink beer (I was a fast learner). The cost of a carton of two hundred cigarettes on the ship was eleven shilling and four pence (tax free of course) BUT the cost of the same carton of cigarettes in the Mina ‘canteen’ was seven shillings and six pence, a huge saving considering that I was paid four pound two shilling and six pence a week, for an eight four hour week – we were not paid overtime.

To say that the purser was upset when we returned to the ship with a number of cartons of cigarettes would be an understatement.

The cost of a bottle of gin on the ship was about eleven shillings, and in the Mina canteen it was seven shilling. Fortunately for the purser, I didn’t like gin.

Inside the canteen it was all plastic chairs and Formica tabletops, everything was utilitarian, because nobody expected sailors to have any taste or finesse. I suppose we didn’t do our selves any favours because most evenings there were fights between different nationalities. Some would say that this was the only way tanker men could let off steam. They were not allowed in to the city, they would not see their wives or girlfriends for months on end and every port they visited was miles away from the population due to the risk of explosion or fire from the cargo that they carried.

When a tanker man could no longer stand the smell of crude oil, or handle the working conditions, he would leave, and his mates would say he had ‘tankeritous’ as if it was a disease.

From my position as a first tripper, I accept that we worked for long hours and didn’t get Sunday off. It was the life style of being at sea at that time. For years after leaving the sea, if I suffered from a heavy cough I could taste the crude oil. Heaven knows what it has done to my lungs.

From Mina we sailed for five days to Little Aden, which was across the bay from Aden, in what today is known as the Yemen. In 1962 Aden and the surrounding area was still under British control. The Crater District of Aden town is situated in a crater of an ancient volcano. This area was the main business area and to walk around for a spot of sight seeing was exhausting in the heat. I doubt that Aden will ever become a ‘must see’ place on anyone’s bucket list. My visit to Aden town was some months in the future when we anchored off Aden to change deck crews and boiler clean. Once again we ‘tankermen’ could not leave the refinery area of Little Aden.

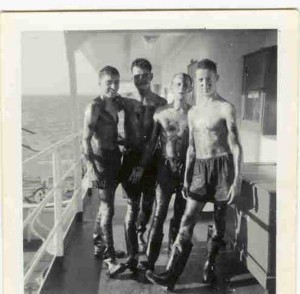

After discharging our cargo it was five days sailing back to Mina during which time we cadets had the unenviable task of supervising the cleaning of all the used tanks – tank cleaning, what a joy, six hours on, six hours off, day after day.

I am second from the left – Health & Safety, what’s that when tank cleaning in 1962. To be fair we were supposed to wear breathing apparatus when we were fifty feet (15.5 mtrs) down a crude oil tank, but it was virtually impossible to climb down the vertical ladders while wearing the equipment, and to work when at the bottom. In the heat of the Persian Gulf we wore as little as possible. We didn’t work down the tank for too long, because the fumes would make one light headed (similar feeling as if one was a little drunk) and ones judgment could be affected and we still had to climb the fifty-foot vertical ladder to the surface.

There was one tradition that we all enjoyed on a daily basis, which was the consumption of fresh lime juice at 11.00 am. This tradition was an obvious a throwback to the avoidance of scurvy when at sea, due to the use of salt as a preservative before refrigeration. It was because of this use of lime juice, during sailing ship days, that American sailors nick named British sailors ‘Limeys.’

In addition to being a welcome break from work, it also quenched ones thirst. The odd thing about this tradition was that we used the lime juice to help us consume two large salt tablets! We had to be careful that we replaced the salt lost due to excessive sweating when tank cleaning. Ironic that we used yesterday’s preventative solution to help us prevent a related problem two hundred years later.

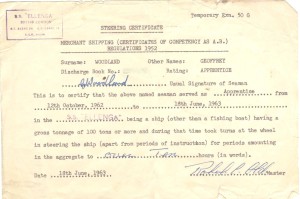

In addition to tank cleaning we were expected to keep up with our studies, via a correspondence course, for the examination for a 2nd Mates ‘ticket’. Certain certificates were required before we would be allowed to sit the examination in the UK, and this included the ability to steer an ocean going vessel correctly.

The Captain soon had me practising my helmsmen skills. During my time at HMS Conway we were expected to gain the ability to handle small boats, which included powerboats, rowing cutters, which had twelve oarsmen, or gigs with six oarsmen, as well as small sailing boats.

After a time one gained the ‘feel’ of what ever craft that you were steering, and a 30,000 gt tanker was no exception, it just took a little longer to alter course, which is an understatement.

While at the helm if the wake of the vessel was not arrow strait the Captain would make him self heard – he didn’t like a zig zag course, because it used too much fuel, and he maintained that because we were no longer a target for submarines, zig zagging was for cowboys.

While at the helm if the wake of the vessel was not arrow strait the Captain would make him self heard – he didn’t like a zig zag course, because it used too much fuel, and he maintained that because we were no longer a target for submarines, zig zagging was for cowboys.

Other certificates that were required before sitting the examination consisted of a Lifeboat man’s certificate, RADAR operator certificate and St John’s Ambulance First Aid Certificate. If a British vessel had ‘less than ninety nine souls on board’ the vessel was not required to carry a doctor, hence the first aid certificate. Of course we had a book called the ‘The Ship Captain’s Medical Guide’ – I still have mine published in 1946, Ministry of War Transport – cost was 3/6d. It has plenty of black and white sketches and photographs to help us remove foreign bodies from eyes, or people.

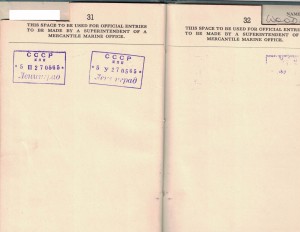

RADAR certificate Lifeboat ticket stamped in my Discharge book

The round trip from Mina to Little Aden, and back again to Mina, was called the Mina / Aden ferry – five days down to Aden and five days up to Mina (tank cleaning). Is it any wonder people ended up with Tankeritous?

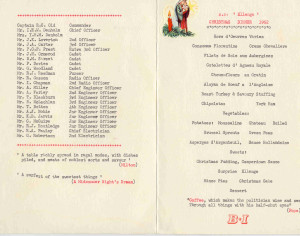

On the 21st December 1962 we loaded once again at Mina, for Little Aden. Christmas Day was celebrated in the Persian Gulf, as we sailed through the Straits of Homuz. The cadets were given a day off, with a very slack day for Boxing Day.

The menu for our Christmas evening meal whilst at sea.

We were off Little Aden wharf at 2.00 am, 27th December and sailed at 4.00 pm the following day. Our departure time from Little Aden allowed us to celebrate New Year Eve and the first day of 1963, at sea, in the Persian Gulf.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

1963

After loading in Mina the Company took pity on us and we were ordered to Philadelphia; to be exact the oil terminal at Marcus Hook, on the Delaware River. We didn’t care where our destination was, as long as it wasn’t Little Aden!

The voyage was twenty-eight days, out of the Persian Gulf in to the Arabian Sea, the Red Sea, through the Suez Canal, and across the Mediterranean, followed by the Atlantic in mid-winter. The winter of 62/63 was the coldest winter in the UK since 1947. In the Atlantic we had to put up with storms, and mountainous seas that smashed in to the ship and twisted metal ladders, while the wind carried away ridged awnings that were bolted to the ship. All galley fires were extinguished and we lived off corned beef sandwiches and hard-boiled eggs for days. Nobody was allowed on deck because of the wind and waves. I’d read about huge Atlantic waves, but being on a 37,000-dwt ship, and being tossed about as if we were a toy boat in a child’s bath, is something else.

The first morning of the storm two of us, in our ignorance, donned oilskins and sea boots (wellingtons), and made our way gingerly along the catwalk. We were going to check on the water in the small swimming pool, which was down aft. The pool cannot be seen in the photo, because the pool was on the starboard side of the aft accommodation.

The first morning of the storm two of us, in our ignorance, donned oilskins and sea boots (wellingtons), and made our way gingerly along the catwalk. We were going to check on the water in the small swimming pool, which was down aft. The pool cannot be seen in the photo, because the pool was on the starboard side of the aft accommodation.

The catwalk is a suspended walkway to allow people to get from the midsection of the ship (officers’ accommodation and bridge area) to the aft area, without climbing over the deck pipes. Most tankers have a catwalk, which are several feet above the deck piping. Along the catwalk are shelters, also known as bus stops, to protect the walkers during bad weather. The idea being to dodge, from bus stop to bus stop, as you moved aft.

The above photograph shows the Ellenga, and the two bus stops aft of the centre accommodation can be seen – they are the two white objects on the deck.

This particular day, once we were outside, we realised how bad the weather had become, but we still stupidly started our dash from the accommodation to the first bus stop. On reaching this shelter a large wave hit us, and green water rolled over the deck covering everything in sight, including the catwalk. We hung on as water poured around and entered the bus stop high enough to fill our sea boots. The ship rolled again, and the water flowed from the bus stop leaving us gripping the safety rail for dear life, and trying to walk quickly back to the accommodation before the next wave hit. Trying to run on a moving deck with you sea boots full of water, is very uncomfortable, and slow. We managed to reach the main door of the air lock just as the next wave started its run across the deck. It took the strength of the two of us to pull open the main door against the power of the wind, and the roll of the ship.

The airlock was a system that would not allow the outer door of the accommodation, and the inner door in to the living area, to be open at the same time. We were allowed to smoke inside the accommodation, so of course we were very careful not to allow fumes or gas from the cargo of oil in to the accommodation. The matches that we used to light our cigarettes were ‘safety’ matches, and normal matches and lighters were forbidden.

The first mate was not at all happy when he found us squelching our way to our cabins. I don’t know if it was due to our stupidity, or because we were wetting the carpet along the corridor.

Eventually we made it to the mouth of the Delaware River and picked up a pilot. I was on the bridge keeping the logbook up to date – every thing that happened was recorded in writing – pilot aboard, pilot on the bridge, when he gave his first order it was Pilot’s advise, Captain’s orders. The Captain was still in command even when the pilot was on the bridge.

I did not record the first comment from the Pilot to the bridge personnel as he walked through the door.

Although we had been at sea for twenty-eight days we managed to keep up with world affairs, particularly those concerning the UK. Harold Macmillan, the British Prime Minister, had his hands full dealing with John Profumo, the Secretary of State for War, the Soviet Naval Attaché at the Russian embassy, and a young woman named Christine Keeler, who was supposed to have been sleeping with the Secretary of War, and the Soviet Naval Attaché, at the same time!

The American pilot threw out the following to those of us on the bridge –

‘What are Christine Keeler’s favourite newspapers?’

Of course none of us knew the answer, but the pilot did –

‘She takes a Mail, a Mirror, a couple of Observers, and as many Times as she can get.’

This caused all the British to burst out laughing, but the helmsman, who was Indian, looked at us as if we were completely mad. He was not aware that the Mail, Mirror, Observer & Times were all British newspapers.

The weather, during our crossing of the Atlantic, was so cold that it was causing the oil to turn to a glutenous mass.

As cadets, it was our job (weather permitting) to lower a thermometer with a cup on the end, which filled with oil and registered the oil’s temperature. If the oil became too cold it would be very difficult to pump ashore. The temperature was recorded and the engineers informed. The engineers would then heat the oil to keep it in a liquid state. At times it was so cold on deck that as we pulled the thermometer up we could see the temperature of the oil, in the small reservoir, falling.

We worked in pairs, and it was difficult to move around due to the layers of clothing and the thick socks and sea boots that we wore, in an effort to keep from freezing. The tanker had thirty-three tanks, of which six were always kept ‘clean’ for salt-water ballast to be used after discharging the oil. Sounding the remaining twenty-seven, in the temperate climate of the Mediterranean took just over an hour. In the cold of the North Atlantic it went on for much longer.

Fortunately the ship’s engineers managed to heat the oil to the correct temperature, and once alongside at Marcus Hook on the Delaware, we started discharging; while the river began to freeze, and lock us alongside.

I managed to get some time off and went by train to Philadelphia. It was extremely cold, which took the edge of any idea of sightseeing. I did buy an original Tommy Dorsey LP for $1, which I still have (music transferred to the computer and cleaned of the original scratches), and also a black fur hat, which came in handy some years later in Leningrad (now called St Petersburg).

Our next move, after breaking out of the ice in the river, was to Maracaibo in Venezuela, for a cargo of oil for the UK. At least it would be warm in Venezuela!

During the voyage we were followed and watched by the US navy, because the Cuba crisis had not long been resolved (about ten weeks earlier) and the US & Russia were still a little ‘nervous’. Nothing untoward happened and we were able to load our cargo in Venezuela and sail for home.

Every time we sailed for a European port we sailed for Lefo – I tried to find this destination on the chart, and in an atlas, but failed. I eventually found out that Lefo is fictional point just off the south coast of England – Land’s End For Orders! Our cargo may have been on sold to another destination.

Having crossed the Atlantic again and having our destination confirmed at LEFO, we entered the English Channel, which was wrapped in thick fog. There is nothing so haunting as the sound of ships’ foghorns to warn other vessel of your closeness. The problem is that sound bounces around in fog and the vessel may not be where you expect it to be. Fortunately my own ship, being only a couple of years old, had radar so we were able to ‘see’ our way up the channel. Even so we were only moving at a very slow speed. According to international sea law, the speed should be such that you can stop in half the distance that you can see.

We arrived safely at the Isle of Grain oil depot at the mouth of the River Thames. A fast discharge and by mid April, we were back in the Persian Gulf at a new loading port called Banda Mashur in Iran, (Some times known as Bandar-e Mah Shahr), where we managed to load at a rate of 4200 tons an hour. We didn’t wish to hang around, and I think this was fastest hourly rate that we recorded.

Some of the other fun places we visited – Das Island, which is a hundred miles (160 km) off the coast of Abu Dhabi; the size of the island is three quarters of a mile by one and a half miles, and is famous as a landing spot for migrating birds and a place for sea turtles to breed. Not a particularly sexy place to visit, but apparently the turtles liked this place as a holiday island.

Ras al Khaimah was another hot spot. Funny, but Ras al Khaimah means ‘top of the tent’; which is the last place I’d think of if I wanted to go camping.

A fast loading and this time we were off to Wilhelmshaven in Germany, via of course LEFO.

In the next few months we focused on Mina; the corrugated canteen, with its joy of the reason for travel, and visits to Little Aden, but all good things come to end and we finally returned to the Isle of Grain where I paid off the tanker, after nearly nine months, and went home to Birkenhead in June 1963.

I was given eight weeks leave, but after two weeks I was bored. The boredom was my fault because I’d changed. I’d seen some of the world, experienced storms, picked up enough Hindi words to make myself understood to our Indian crew, and could now steer an ocean going vessel. I was even beginning to miss the Mina / Aden ferry I was in a bad way.

My friends back home hadn’t changed. They spoke of last night’s TV, football at the weekend, and they looked forward to their annual holiday.

There was nothing wrong with their life, but it wasn’t for me, after all, I doubted that I would have any reason to go ‘abroad,’ didn’t I say that at school?

The thought of another six weeks of boredom was too much, so I rang the Company and asked for a ship.

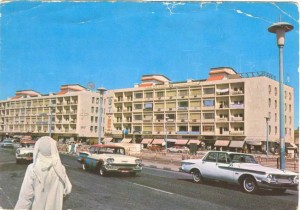

The Company obliged, and sent me an airline ticket for Kuwait!

I left Heathrow on a Comet 4 for Rome, next stop should have been Damascus, but we were diverted to Beirut, and finally Kuwait. On landing I was met in the arrival hall by a representative of the shipping agent and within minutes I had my bag and was through customs and immigration, while many other passengers were still queuing. Outside I was escorted to a very large American car; the driver opened the rear door and indicated that I should sit in the back. The agent shook my hand and wished me a safe journey, which at the time I thought was a strange comment. After all we were only going to a city hotel. The driver smiled at me, via the rear view mirror, and put his foot down on the accelerator. Now I understood the agent’s comment, within minutes we were travelling at over one hundred miles an hour along a freeway to the city. At that time nobody wore seatbelts. I just hung on to the roof strap. Thirty minutes later we pulled up at the Bristol Hotel in a cloud of dust and sand. I was to wait in this hotel until my ship arrived in to Kuwait.

I sent this post card to my parents to let them know that I’d arrived safely. At that time we did not have a phone at home, and e-mail was thirty-five years in the future.

It was mid July and I only ventured out of the hotel in the early morning or late afternoon – it was the height of summer and it was HOT & dusty. The hotel was ‘dry’ i.e they were not allowed to sell alcohol, so one couldn’t have a cold beer in the cool of the evening.

I received a phone call at 4.00 am, and I thought it was the agent telling me that my new ship had arrive – wrong number. I received another at 10.00 am and this time it was the agent to let me know that I would be collected and taken to my new ship in the early afternoon, the Landuara.

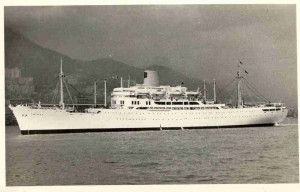

What a difference between this vessel and the tanker. The tanker was just over two years old, and my latest posting was to a vessel that had been launched in 1946, two years after I had been born. Her deadweight was 7200 tons. She didn’t have any air-conditioning, cadets slept two to a cabin, and the cabins were not at all large, in fact the shared cabin was smaller than the single cabins on the tanker.

Our first port of call, after leaving Kuwait, was Basra, about 60 miles up the Shatt al Arab. Many people refer to it as the Shatt al Arab River, but the Arabic meaning is Stream or River of the Arabs, so by putting river at the end we have Stream or River of the Arabs River, which is a bit of a mouthful.

The river itself denotes the border between Iraq and Iran, and it is the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates. Basra is about as far upriver as a sea going vessel can reach from the Persian Gulf.

The river flowed through miles and miles of Iraqi and Iranian desert. Khaki was the colour of the day, in fact every day. Sand storms, along with the heat and the flies made this area of the world one of the most unattractive. From memory the only green things I ever saw were the leaves of palms, and the lawn of the British Club, which was not the lush green of England, but a pale green / yellow effort that stood little chance of ever turning a lush green in the searing heat of August. The Shatt al Arab water was a dirty brown combination of local sewers, run off from the surrounding land after oxen had walked in circles to drive water from the river to irrigate the riverbank area, and the occasional shower of rain. It was unthinkable for any of us to wish to swim in such water, walk on it perhaps, but never in it to swim.

I did hear once that where the Tigris and the Euphrates meet, is where the Garden of Eden is supposed to have been located. Things have changed in the area since Adam and Eve left the garden.

By now it was August the hottest time of the Iraq summer and temperatures during the day were well over the 40 c (106F) mark and when working in the holds of the ship, the temperatures were higher again. At night I used to obtain two very large bath towels, soak them in a bath of fresh water, and put one on the deck of the highest part of the ship, and pull the other over me in an effort to get some sleep before either towel dried out. Sleeping in the cabin was impossible, because of the lack of air conditioning. We did have a small fan, but all that did was move the hot air from over there, to over here, without generating any cooling.

When I was in my fifties I suffered from rheumatism in certain weather conditions and I blame the use of the soaking wet towels as the cause – but without the wet towels we wouldn’t be able to get any sleep. Imagine the conditions for our engineers when they were on duty in the engine room.

At the end of the workday (we were alongside, not moored in the river) we did have the chance to visit the British Club, where we could buy English beer. The members allowed us to use their swimming pool, and they were very kind and friendly to us poor cadets making us ‘honorary’ members. The other advantage of the British Club was that a number of the members had their daughters visiting during the British school holidays (late July to early September), and some of the daughters were my age. . . . . but we were not going to step out of line and cause any problems, after all the Club had been very kind to us, and they sold cold beer.

On the evenings that we didn’t go ashore, we would sit outside our accommodation on the riverside of the ship, not the shore side, and eat watermelon, and hold pip-spiting contests across the river – we never reached the other side. The melons were obtained via barter. Wood in Iraq was expensive and difficult to obtain. Our ship used wood as dunnage when stowing cargo during loading cargo (well before containerisation), because it was inexpensive or a waste material from another process. After we had unloaded cargo we would always have plenty of dunnage left over, and we either dumped it at sea (forty years before the PC brigade were invented), or reuse some of the dunnage for the next time we loaded cargo. Our old dunnage had value to the local Arabs, so we would swap some for huge watermelons that grew along the banks – we were happy and the local Iraqi boatmen were happy.

After completing our unloading and the loading of export cargo (dates), we dropped down the river to Khoramshah, which is on the Iranian river bank, so we had to remember to refer to the Shatt al Arab as the Arvand Rud (Swift river), which is the Persian (Iranian) name for the river. Instead of watermelon pips we swapped dunnage for pistachio nuts; we didn’t spit, but flicked the shells across the water. Iran, being the largest producer of this nut ensured we had a regular supply.

Finally we were free of the river, and out in to the Persian Gulf. If we visited an Arab port it was the Arabian Gulf never the Persian Gulf, but we didn’t care as the movement of the ship created its own breeze, however hot, and Bombay in India was our next port of call.

Gateway to India (from a post card)

I liked Bombay with its teaming millions, garri wallhas (motorised rickshaw now commonly called tuk tuks), honking horns, the ringing of bicycle bells, and the ever mouth watering smell of spiced food.

I’d grown to love curries, because at lunchtime on the Company’s vessels, the officers would be offered curry (as well as European food). The curries were different every day, from beef through to fish or vegetables. We had two galleys on the ship (sometimes more if we had Muslim & Hindu crews), one for the European officers and the other for the crew. The deck crew might have all been hired from one village in India or Pakistan, and the engine room crew from another village. The cooks and stewards for the Europeans were Goanese, which was a colony of Portugal until 1961. The Indian cooks might have been Muslim or Hindu, which meant that the officers would not be able to eat their bacon (Muslims will not touch pig meat) and eggs, or their roast beef (Hindu will not touch cow meat), so the solution was to hire people from Goa to attend to the officers, because they were generally Catholics, due to the influence of Portugal, so everyone was happy! The Goanese Company cooks produce great curries.

Bombay was a major location for the Company, having traded around the Indian coast for over a hundred years. This port had a Company Officer’s Club, which were part hotel, and part social club i.e snooker, cards etc and a small bar. The hotel part would be used by officers waiting for their ship to arrive, as I did in the Bristol Hotel in Kuwait.

On my first visit to the Club I entered the bar to see people drinking beer, so I asked the barman for a cold beer.

‘Chitty, Sahib’

On the ship one didn’t use money, but signed a chit for a case of beer or a carton of cigarettes.

‘Chitty?’ I asked.

‘From the police, Sahib’

At this point a fellow officer took pity on the new boy and explained the system. I had to report to the police and fill in a form stating that I was an alcoholic, and I would be given a chit allowing me to buy a limited number of beers at the Officers’ Club. Maharashtra State, in which Bombay was located, was a ‘dry’ State! (It isn’t now). So it was pure panic to get to the police station before the senior officer went home for the night. I managed it! I wonder if I am still listed as an alcoholic in this part of India.

Outside, in the city away from the Raj like atmosphere of the Officers Club, one could get a large beer (650 ml) in the brothels (none of us wanted the ladies) for about ten shillings, which was very expensive, but better than nothing in the humidity of Bombay after we’d finished our small beer allowance sanctioned by the police. After ordering the beer we always wanted to see the un-opened bottle so that we could inspect the cap and make sure it had not been tampered with in anyway. I must admit the establishment made sure that they didn’t offend anyone (very PC for those days). Around the walls of the ‘ladies waiting room’ were pictures and photographs of most of the world leaders from, Queen Elizabeth (UK), JFK (US), Archbishop Makarios of Cyprus, Khrushchev (USSR), Charles de Gaulle (France), Franco (Spain) and Pope John IIIX, few leaders were left out. To me it was an eye opener to another world. The ports visited by the tanker were very restricted compared to my current tramp ship.

I did hear it say that the Bombay beer, at that time, was brewed from onions, but I am unable to confirm this as fact, but after seeing people drink a few bottles of the local Bombay brew, many would often start crying, so the theory might be true!

Our next port of call was Cochin, (now called Kochi) in the state of Kerala, which is located on the southwestern coast of India. At that time Cochin was a small quiet port with little industry. I cannot remember if our visit was to offload cargo or pick up cargo, but I think that we were the only vessel in port. We were alongside a small concrete wharf, and not there long enough to do much exploring.

The little exploring that I did lead me to a dusty street where a lone man was painting in water colours. His style of painting was mainly in a sepia format. As you can tell my knowledge of art is limited to say the least. I got chatting with the painter and he told me that he only painted local scenes and mainly in blue – black, green- black etc. I looked at some of his completed works and bought four pictures, which included the one he was painting at the time. I purchased three sepia pictures, one green, one blue, one brown and the fourth was a multicoloured picture of a river scene. The three sepia pictures were all different riverbank scenes with silhouetted trees. The man was happy that I paid the asking price, which worked out at about 2/6d each. It was not until I married that I had them framed and mounted with non-reflecting glass. They have been on our dining room wall, in a block of four, in every house in which we have lived since 1969.

We only stayed in Cochin for twenty-four hours and the following morning I was sent to find the draught of the ship. This required me to check the numbers on the bow and stern and estimating the drought. The size of each number was six inches and the gap between each number was six inches, so estimating the drought didn’t take any great skill. As I walked back from the bow to the gangway I spotted something in the water between the ship and the wharf. I looked over and saw that it was a body. Perhaps he had been carried in on the tide. I shouted for the Indians on the wharf to bring a boat hook, and something to move the body to the end of wharf where there was a ladder, and hopefully we could lasso the deceased. Using long pieces of wood the body was moved to the end of the wharf, and by this time I had quite an audience. Holding on to the ladder I grabbed for the body’s arm. It came away in my hand. I was so surprised I dropped the arm back in to the water, but fortunately at that moment a small boat came around the bow of my ship and pulled the remains out of the water. I climbed back on to the wharf and reported back on board and made my way to the bathroom and scrubbed my hands nearly raw. A few minutes later the gangway was hauled on board and we sailed for Tutticorin.

I came, I saw, and I left, this is all that I can remember of Tutticorin. We anchored off the town and small boats came out to us, and using our own derricks we completed unloading / loading the small amount of cargo. I think our total time off this small town was about eighteen hours.

We sailed across the Bay of Bengal to the small island of Penang, which is off the west coast of Malaysia. I have always liked this island, and I have enjoyed every visit. After my visits in the 1960’s, I left the sea in 1969, and not until 2005 did I return to Penang, and have been back a number of times since.

To work cargo in Penang the vessel was moored to a buoy; junks and barges came out to us, and we used our own steam derricks to unload the cargo, and reload fresh cargo. Everything was very labour intensive. We didn’t work night cargo so from a cadet’s point of view the longer we took loading the more time we had in the evenings enjoying Georgetown, which is the capital of the island.

Local transport was the rickshaw pulled by, usually, an old man, or someone who seemed very old to this nineteen year old. The ‘Coolies’ didn’t have an once of fat on them and appeared to be all muscle and sinew. There were also trishaws – three wheeled bicycles with rear seats for the passenger and a cover to keep off the sun or rain.

One evening three of us persuaded three trishaw drivers to allow us to ‘have go’ at being the driver. We put our passenger (the driver) in the back and set off. It was hard work even for a reasonably fit nineteen year old. I cannot remember if the driving system had gears. All I know is that we came to the top of a small hill and decided to race to the bottom. We charged down the hill with the drivers shouting and gesturing, we were not sure if they wished us to stop, or they were shouting encouragement, because being Chinese they’d decide to bet on each of us to win.

At the bottom we managed to stop the machines and return them to the drivers with a handsome tip for the ride. My legs ached for hours afterwards.

We slipped our cable from the buoy and turned south towards Singapore, where we would take part in a historic event.

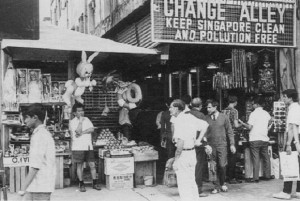

Arriving in Singapore on Saturday the 14th September 1963, the cadets were allowed to go ashore and have a swim at the Seaman’s Club. Again the ship was anchored off the wharf area, and we would take a small junk and be rowed, usual by a female using the single paddle at the stern of the junk, from the ship to Clifford Pier near Change Alley. Sunday the 15th was a day of rest us, as well as all of Singapore, because that was the day the festivities would start. On the 16th September 1963 Singapore would join Malay to create a new country called Malaysia. The British were no longer in charge of Singapore.

Singapore in the 1960’s was as ‘foreign’ as one could get – it was a mixture of British, Malay, China, Indonesia, and everywhere else in between – it was Asian, and I loved it from the minute I set foot ashore on Clifford Pier.

Clifford Pier – still there today, but it is now a museum, I think.

First thing we always did on crossing the road, known as Collyer Quay, was to visit Change Alley – at that time famous for money changers. Now it is an upmarket, air-conditioned shopping area.

With ‘Sing’ dollars in our pocket one could not go past the Cellar Bar, which was below street level (obviously), and a cool, quiet place (being late morning) for a cold Tiger beer. It would liven up at lunchtime and in the evening.

To illustrate how important the Cellar Bar was to the seafaring fraternity, I will jump a head from 1963 to 1966.

After I’d finished my time as a cadet, and passed the exams for a Second Mates ticket I was sent, in April 1966, to Singapore to join an LST (Landing Ship Tank) as third mate. The Company had the contract to supply officers and crews for the various LSTs controlled by the British Ministry of Defence around the world. From 1962 to 1966 Malaya and Indonesia had been fighting an undeclared war, which dragged Britain, Australia & New Zealand in to this ‘confrontation’.

I joined LST Frederick Clover, which was built in 1945 as LST 3001, and named ‘Frederick Clover’ after the war, gross tonnage 4225, so not a particularly large vessel.

I joined LST Frederick Clover, which was built in 1945 as LST 3001, and named ‘Frederick Clover’ after the war, gross tonnage 4225, so not a particularly large vessel.

Our duties were to carry supplies and troops (the troops to and from) Borneo in support of the fight against Indonesia.

LST 3001- 1945/6

There were other LSTs on similar runs to Borneo, and the officers used to socialise at the Cellar Bar whenever their ship was in port. One day I asked, at the naval office, when a particular LST would be in port, because the third mate in this LST was a friend of mine. I was told that they couldn’t tell me because I wasn’t security cleared, and the movement of the LSTs were on a ‘need to know’ basis. I even explained that I was part of the LST fleet, but as I was still a merchant seaman, rather than Royal Navy, they couldn’t help me, although I’d signed the Official Secrets Act in case I gave away the top speed (10 kts) of the Frederick Clover.

Not a problem, my next stop was the Cellar Bar and I asked the girls behind the bar if they knew when my friend was due in Singapore. They were quite happy to tell me the name of his LST, and that he was due into Singapore the following day!, so much for ‘need to know’, and naval security.

Let’s move back to the celebrations of Singapore joining Malaya, to create the new country of Malaysia.

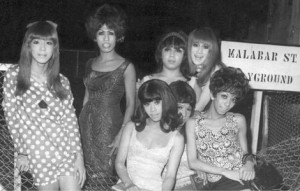

Early evening we visited Bugis Street for something to eat – the place was already ‘jumping’. Bugis St was famous for the food stalls, beer halls and ‘girls’, although many were not female, but males dressed as females. The ‘trans’ girls would parade up and down the street in their finery and offer to sit near or on someone’s lap while photographs were taken. For this service ‘she’ would charge a small fee. If they worked the street for a number of hours they would earn a very good living. It was known that certain first tripper boy seamen, around fifteen or sixteen years old would be caught up with the whole ambiance of Bugis St and slide off with one of the very attractive ‘attractions’. It didn’t take long for his mates to see the young first tripper running like mad towards them, as if the hounds of hell were after him. His introduction to Bugis Street nightlife was not what he expected.

Early evening for food and beer.

Around mid-night the ‘girls’ would show up.

Anybody wish to take my photo?

How to tell the difference between the ‘she’ men and real women? The real women couldn’t afford to dress as well as the ‘she’ men. I was always told to check the Adams apple on the ‘women’ – but I never got that close!

The celebrations went on for a few days, but the ‘marriage’ of Singapore and Malaya didn’t last. It was all over by the 9th August 1965, when Singapore became an independent state. This was still in the future.

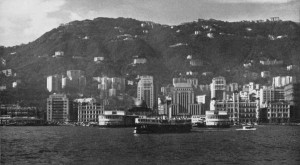

Our next port was Hong Kong. We anchored in the harbour on the 21st September, just a week after entering Singapore harbour.

Once again the smell of Asia fired my imagination of day’s gone bye. They do say that you can smell money in Hong Kong – everyone is after their share.

Bum boats surrounded the ship offering everything from sew sew girls, who actually did repair clothes, washer women who promise fast turn around of your laundry, food boats offering hot (heat hot and spice hot) food with a cold drink for a very cheap price, haircut and a free shave, there seemed to be a boat for everything. The smaller boats rowed by a single oar at the stern, operated by a female, the richer boats had small engines. Taxi boats came alongside to offer a ferry service to Hong Kong Island or Kowloon. Rates were discussed and bartered until we all had an understanding of the ‘correct’ fee for the trip ashore.

Similar to Singapore we were at anchor and worked cargo in to junks and barges. Everything that we required from fresh water to frozen food and fresh vegetables had to come out by boat. Very few ships had the ability to turn seawater in to fresh water. Working cargo, while at anchor, occurred in so many ports from the Persian Gulf to the harbours of Penang, Singapore, and Hong Kong that we never found it strange.

The Star Ferry operated between the island and the mainland (Kowloon) and seemed to take quite a while to complete the run. I returned to Hong Kong in 2006 and due to land reclamation the trip today is much shorter and some how not as romantic.

The Star Ferry operated between the island and the mainland (Kowloon) and seemed to take quite a while to complete the run. I returned to Hong Kong in 2006 and due to land reclamation the trip today is much shorter and some how not as romantic.

Hong Kong in the 1960’s

Hong Kong forty years later in 2006

Of course we’d seen the film ‘The World of Suzie Wong’ and we’d read the book, so we had to find Suzie Wong during our short stay.

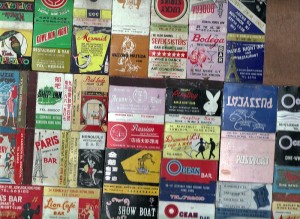

We covered as many bars as we could find. We worked all day on the ship, and partied most nights. At nineteen one had stamina! Every bar we entered offered us a box or book of matches, after all most of us smoked in those pre PC days. Smoking was virtually compulsory considering the very low price of cigarettes, which were duty & tax-free on the ship. Samples of the matches from some of the bars are shown in this picture.

We did find Suzie’s bar . . . not a bit like I imagined.

We were not on holiday and could only get ashore in the evening, so we didn’t spend every spare minute checking out the bars, but did manage to get to the Peak via the Peak tram. Even these sites have changed – even the green trains are red, (or where in 2006) and the view has changed somewhat.

After two days working cargo, the clanking of the anchor chain, as we weighed anchor, heralded our departure. We were off again, and this time to Japan.

The short voyage, via the Straits of Formosa, took us six days and we anchored off Yokohama. The quarantine authorities would not let us go alongside until they had checked all officers and crew via stool sample for various diseases. We were issued with very small ice cream cups in which we had to place the sample and seal the container. The samples were collected and rushed ashore – I have no idea what they did with the samples, but we were allowed alongside the following day.

Yokohama, in Tokyo Bay, was our first port of call of our coastal trip around Japan. If I thought Singapore and Hong Kong were foreign, Yokohama was real ‘foreign’. The people were different from Chinese, very friendly, but different. Fortunately at that time the exchange rate for a British pound note was 1060 Japanese yen. The current exchange rate is 172 yen for a British pound. How the mighty have fallen.

At least this time we were alongside, and we didn’t have to worry about shore boats, just taxis getting in to & out of the dock area so that we didn’t have to walk too far. We were alongside for three days, and the evenings were spent in the town, but as time passed I realised that even at the fabulous exchange rate I was running out of money. My weekly wage was about £5.00 a week and a taxi to / from the city was expensive. I didn’t see much of Yokohama city except in the evening when it was dark. Being October the sunset came early.